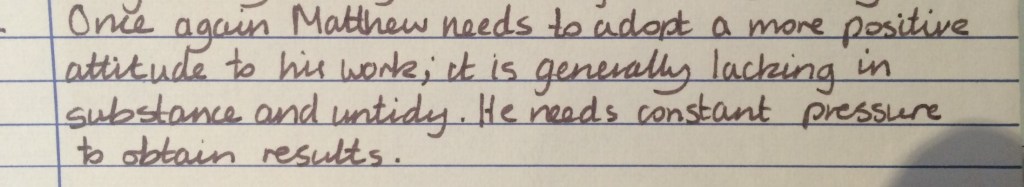

If I were to write a report on our efforts over the years to master the subject of school improvement, I might choose similar words to those (above) once levelled against me. Our thinking on the matter is generally lacking in substance and untidy. And given the high stakes accountability framework we have created, an outsider looking in could be forgiven for assuming that constant pressure is indeed the only way to obtain better results.

But, in the words of many a school report, we must do better. I am willing to take the advice offered to my 14 year-old self to adopt a positive attitude towards this problem. School improvement as a professional endeavour need not be left to the whim of headteachers, the personal preference of consultants, or the ideology of Ofsted or the DfE. If we are intentional and determined, we can build a better knowledge base – one which is organised and substantiated. But to do so, we must mobilise as a body of professionals.

And we must set a high bar for what we accept as valid and for how we set about the task.

A high bar for evidence

To be successful as a discipline, a profession has to claim a knowledge base that is sufficiently abstract for it to perpetuate itself and carve out a niche that no other profession can fully address.

Surveying the Landscape of School Social Work Practice

Yesterday, Jen Barker shared an extract from a book she is reading which struck a chord with me (quoted above). Although in the field of social work, the book draws on writings about how professionals go about building an identity and knowledge-base. The authors point out that “professionals do not passively wait for their abstract knowledge base to collect”. Instead, they embark on a “professional project” (Larson, 1977) to establish and control access to a knowledge base which underpins the skills practitioners in the profession require to practice.

Where is our professional project? I see it in the researchED movement; I see it in the educational research community; I see it in attempts by a community of inquisitive educationalists to critique, distil and curate a body of knowledge about school improvement; I see it in the work of organisations working to develop better professional development. There are many out there working on this professional project, possibly more than at any time in recent history. How do we mobilise these efforts to greater effect?

Perhaps part of the answer is to raise the bar for curation, by which I mean being selective and cautious about what knowledge crosses the threshold into our professional canon of work. We are all too ready to claim ‘evidence shows that’ our desired school improvement strategy is the right one, but often the evidence is found to support the action, not to inform it. So too do we reach for evidence based interventions from research supermarkets like the EEF without taking the time to understand what the research does and does not support by way of school improvement actions. We should treat evidence as a clue, not a conclusion. Ultimately, nothing is proven in education, little can be said with a high degree of confidence, and most of our claims are highly contestable. Holding ideas lightly should not paralyse us – we must make a bet on a course of action – but it should caution us against equivocality.

Raising the bar for evidence means asking ‘on what grounds are you making that claim?’ and ‘how likely are you to be wrong?’

A high bar for discourse

Our professional project is a social endeavour. New knowledge is created through discourse between interested parties. Those engaging in this discourse have a responsibility for setting a high bar for themselves and others.

First, we should think carefully about what we choose to talk about. Discourse can easily be steered off course, distracted by unsubstantiated claims, ideological rabbit holes, and whimsical debates (like the recent pen wars on Twitter!). The more we focus on what matters, the more our professional project will thrive.

Second, we should be selective in what we claim to be true and correct. It is easy to preach, but the more we cry wolf by using a voice of certainty, the less others will believe us when we have something important to contribute.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, we must expose our claims to scrutiny and invite others to do so. This requires that we set out our thinking clearly for others to pick apart. Such actions make us vulnerable and we cannot expect this of each other unless, as a community of professionals, we commit to be kind, which means aiming for…

A high bar for respectful debate

The measure of our professional maturity is in how we choose to disagree.

Respectful debate means exercising caution in how we characterise each others’ positions. It means actively resisting polarisation. It means engaging in positions (and with people) you most strongly disagree with in an attempt to establish common ground.

Respectful debate does not require appeasement or the sacrifice of strongly held views. On the contrary, it is respectful to others if you state candidly what you believe and where you differ. When weak minds come together they make no progress, but when strong minds choose to wrestle rather than throw punches, they, for a time at least, merge their intellectual might.

A high bar for action

The test of our ideas is to implement them. At some point, we must move from discourse to take action in our schools. How we choose to inflict our ideas on reality will determine both their worth, and ours.

Our professional project does not stop at the school gates. Those we ask to do the legwork of school improvement are as entitled to engage in respectful discourse as are the wider community of educational thinkers. Our school improvement theories must be treated as hypotheses, their validity tested through open dialogue between colleagues, and open to constant revision as they meet the test of implementation. We must be ready to change our plan, which means being ready to change our mind.

A high bar for impact

Too much so-called school improvement work results in no significant or sustained school improvement. Knowledge of what doesn’t work is as valuable, if not more so, than knowledge of what works. We cannot call ourselves a profession if the knowledge we employ is impotent. If things don’t improve, then school improvement is no more than a passtime; a frivolous diversion from the day job; bullshit work. It often feels that way.

Our professional project is about walking the walk as well as talking the talk. If we can’t improve schools then we invite others to put us under pressure to do so. If our work is generally lacking in substance and untidy, who can blame them?

If we join together, we can mobilise our efforts around a professional project for school improvement. We can do better than what has gone before if we adopt a higher bar for evidence, for discourse, for respectful debate, for action and for impact.

If you want to join this professional project, read this by Ruth Ashbee. Her call to shake up school thinking is one I support. You may disagree. The way we choose to do so is what can unite us.